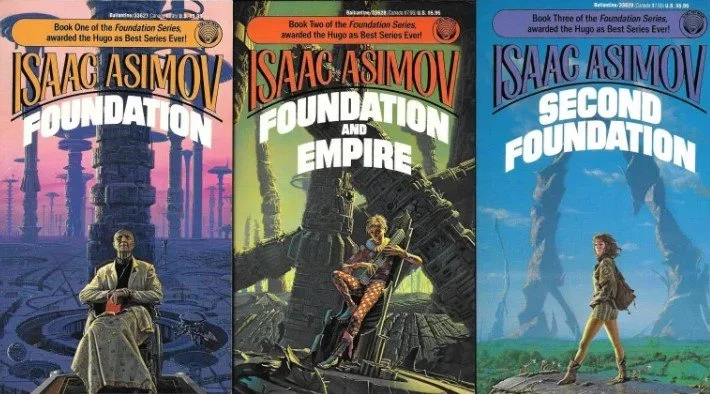

ASIMOV, FOUNDATION & THE WEST

The Asimovian Solution to Civilisational StagnationFoundation is like an alternative conclusion to Edward Gibbon’s ‘The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire’.

Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series is often remembered as a work of science fiction about prediction, mathematics, and empire. Read more carefully, it is something more austere and more instructive. It is a meditation on civilisational stagnation, and on the limited set of tools available to arrest, compress, or survive it.

Asimov was explicit about his inspiration. Foundation was written in conscious dialogue with Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Gibbon’s great work is not a morality tale. It does not argue that Rome fell because it became decadent or immoral. It argues that Rome stagnated because its institutions hardened, its peripheries weakened, and its administrative complexity outpaced its adaptive capacity. Decline was structural, not ethical.

Asimov accepted this diagnosis. The Galactic Empire in Foundation does not fall because it is evil, stupid, or corrupt. It falls because it has become too centralised, too refined, and too brittle to respond to a changing technological and economic environment. The Empire still possesses immense intelligence, culture, and power. What it lacks is the capacity for renewal.

This places Foundation squarely within the logic later articulated by Cardwell and refined by Joel Mokyr. Mature civilisations tend toward stagnation not because they cease to innovate entirely, but because their institutions evolve to protect stability rather than enable transformation. The centre becomes optimised for preservation. The frontier withers. Renewal becomes politically and economically impossible.

Hari Seldon’s intervention does not attempt to save the Empire. That is the first and most important point. Seldon accepts stagnation as inevitable. Psychohistory does not offer prophecy in the mystical sense. It is a theory of scale. At sufficiently large populations, individual agency averages out and structural forces dominate. The question is not whether decline can be prevented, but whether its consequences can be shaped.

The Foundation is Seldon’s answer. Crucially, it is not a government. It is not an ideology. It is not a reform movement. It is an institution designed to preserve and propagate technological and organisational capability at the frontier while the centre decays.

The Foundation is established at the edge of the Empire. Its power does not derive from legitimacy or force, but from indispensability. It controls knowledge, production, logistics, and technical expertise. It trades capability for influence. It embeds itself in local economies and political systems by solving real problems faster than rivals. Power flows toward it not because it claims authority, but because it becomes the infrastructure upon which others depend.

This is the core insight that makes Foundation enduringly relevant. Civilisations do not renew themselves through better ideas at the centre. They renew themselves through new institutions at the frontier. These institutions are almost always infrastructural. They organise energy, trade, production, and logistics. They create new cities, new ports, and new economic interfaces. They allow creative chaos to operate at scale, outside the rigid constraints of mature systems.

Historically, the closest real-world analogue is not a state, but a chartered company. The British East India Company did not exist to reform Britain’s political institutions. It existed to build frontier infrastructure. In doing so, it retrofitted existing cities toward global trade and founded new port cities designed to sit at the boundary between old and emerging economies. Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, Singapore, and later Hong Kong were not accidents of geography. They were instruments of renewal.

Asimov understood this intuitively, even if he expressed it fictionally. The Foundation functions as a civilisation-scale infrastructure project. It seeds new urban nodes, new production systems, and new trade networks while the old order collapses under its own weight. It does not reverse decline through central reform. It routes around it.

There is an important limitation in Asimov’s model, and acknowledging it strengthens rather than weakens the argument. Psychohistory underestimates contingency, individual agency, and the role of conflict. Later volumes in the series grapple explicitly with this flaw. Real history is messier than statistical smoothing allows. Frontier institutions are contested, captured, and sometimes destroyed.

But this does not invalidate the core insight. It clarifies it. Civilisations cannot predict their way out of stagnation. They can only build their way through it. Renewal requires physical systems that tolerate failure, absorb volatility, and scale faster than legacy constraints can suppress them.

Read in this light, Foundation is not a fantasy of control. It is an argument for decentralisation, frontier-building, and infrastructural power. It accepts the limits of reform and focuses instead on the creation of new spaces where creative chaos can operate productively.

This is why the book resonates so strongly with contemporary questions of the future of the West, cities, infrastructure, and technological frontiers. Whether the frontier is maritime, industrial, digital, or orbital, the logic remains the same. Civilisational renewal occurs where institutions are light enough to adapt, dense enough to scale, and concrete enough to matter.

The danger facing advanced civilisations is not sudden collapse, but quiet regression. Dark ages are rarely announced. They arrive gradually, through the slow erosion of capacity, the hollowing out of institutions, and the inability to build at scale when new realities demand it. By the time decline is visible, the frontier has already moved elsewhere.

Asimov’s warning, drawn from Gibbon, is therefore not speculative. It is practical. Civilisations that fail to create new frontiers, new cities, and new infrastructure before stagnation sets in do not renew themselves. They fragment. Knowledge thins. Trade contracts. Technological capability becomes decorative rather than generative. What remains is memory without momentum.

Avoiding our own dark age does not require prophecy or ideology. It requires construction. It requires deliberately opening spaces where creative chaos can operate at scale, where new institutions can form without being smothered by the constraints of the old, and where infrastructure is built fast enough to absorb the technologies that are already reshaping the world.

History offers no second chances at this moment. Civilisations that hesitate do not get to try again later.

They are replaced by those who were willing to build first.

![ROMULLUS | [Sci-Fi] Infrastructure for the West and Her Allies](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/65b3c1f0a4d6295a6ebd4b19/d4a8aeab-602b-41b7-b59f-958880d76a5b/ROMULLUS-61.png?format=1500w)