THE ‘BITTER LESSON’ FOR CIVILISATION.

How AI + Civilisations Escape StagnationThe bitter lesson is based on the historical observations that 1) AI researchers have often tried to build knowledge into their agents, 2) this always helps in the short term, and is personally satisfying to the researcher, but 3) in the long run it plateaus and even inhibits further progress, and 4) breakthrough progress eventually arrives by an opposing approach based on scaling computation by search and learning. The eventual success is tinged with bitterness, and often incompletely digested, because it is success over a favored, human-centric approach.

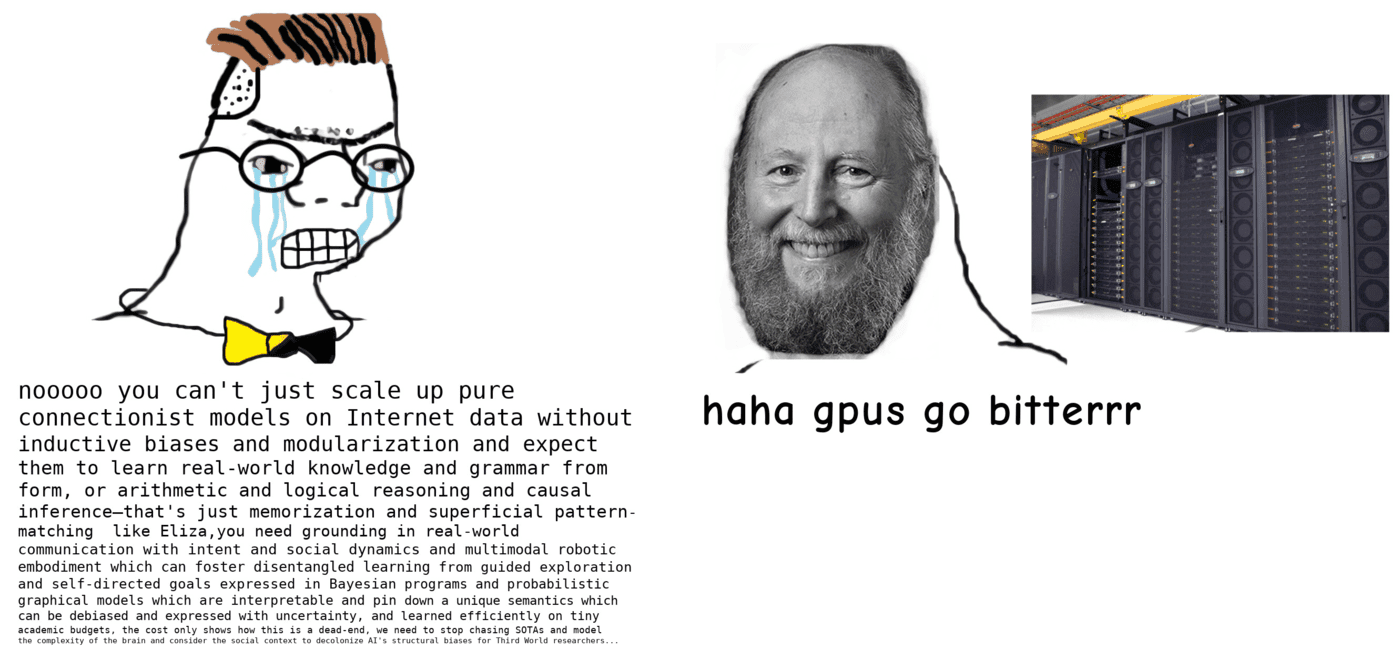

In artificial intelligence research, the “bitter lesson,” a term coined by the computer scientist Rich Sutton (pictured in meme), refers to a hard-won empirical truth. Systems that rely on scale, general methods, and learning from experience consistently outperform systems built around handcrafted intelligence, bespoke rules, or elegant theory. Again and again, approaches that appeared crude but scalable defeated approaches that appeared refined but brittle. Progress did not come from cleverness alone, but from systems able to absorb reality at volume.

This lesson is uncomfortable precisely because it runs against human instinct. We admire brilliance, design, ideology, and optimisation. Yet the evidence is clear. What wins, over time, are systems that learn faster than their rivals because they are bigger, more adaptive, and more deeply embedded in the real world.

The same lesson applies far beyond machines. It applies to cities. It applies to institutions. It applies to civilisation itself.

Once we widen the lens from algorithms to societies, the historical record becomes unambiguous.

Ancient Athens produced extraordinary intelligence, philosophy, and art. It did not produce institutions capable of scaling power across a continent. Rome did. Roman success was not a triumph of superior culture or ideas. It was a triumph of roads, ports, law, logistics, and administrative replication. Rome could move grain, troops, and authority across vast distances. Athens could not. Intelligence without scalable infrastructure lost to infrastructure with sufficient intelligence.

The Italian city-states of the Renaissance present a similar pattern. Florence, Venice, and Genoa were centres of finance, design, and brilliance. Yet their political and economic structures were optimised for refinement rather than expansion. When Atlantic powers built oceanic fleets, global ports, and imperial logistics, Mediterranean sophistication was eclipsed. The future belonged not to the most beautiful cities, but to those that could project power through infrastructure.

Britain’s own history is perhaps the clearest illustration. By the late seventeenth century, England was not the most populous, wealthy, or culturally advanced power in Europe. What it did possess was a growing ecosystem of institutions capable of scaling risk. Chartered companies, maritime insurance, joint stock finance, naval logistics, and port cities formed an adaptive machine that could exploit new realities faster than rivals. The British East India Company mattered not because it was clever, but because it created infrastructure that turned uncertainty into throughput.

The same pattern appears in the American frontier. The westward expansion of the United States was not driven by ideology alone. It was enabled by canals, railroads, land law, ports, energy systems, and eventually oil. Gold rushes mattered less for the gold they produced than for the institutional scaffolding they left behind. Towns, banks, courts, transport corridors, and industrial capacity followed. Scale came first. Refinement followed later.

The inverse pattern is equally consistent. Societies that over-invested in central planning, aesthetic coherence, or ideological purity repeatedly failed. From imperial China’s periodic inward turns to twentieth-century command economies, the story is consistent. Systems optimised for control struggle in environments defined by uncertainty. Systems designed to absorb chaos outperform those designed to suppress it.

This historical pattern brings us directly to the present.

Modern Western societies possess extraordinary intelligence, scientific capability, and design talent. What they increasingly lack is scalable infrastructure that can metabolise new realities at speed. Housing systems that cannot grow. Energy systems that cannot expand. Cities that cannot build. Institutions that fear risk more than stagnation. The result is not decline through defeat, but paralysis through friction.

The stagnation of cities is a particularly acute problem because they are a civilisation’s metabolic organs. They concentrate energy, labour, capital, and information, and convert them into output at scale. When cities are flexible, civilisation accelerates. When cities become rigid, civilisation stagnates, regardless of how sophisticated its culture or governance appears.

This explains a recurring paradox in history. Periods of stagnation often coincide not with intellectual decline, but with institutional over-refinement. Rules multiply. Planning becomes prescriptive. Risk is suppressed in the name of order. What emerges is a brittle system optimised for yesterday’s conditions and incapable of responding to new technological or economic realities.

Much of this rigidity is not accidental. Modern policy and economic frameworks are often the product of historical trauma: war, depression, financial collapse, inflationary spirals. Like scar tissue, they form to prevent the recurrence of past injury. In doing so, they stabilise the system and preserve hard-won gains. Yet over time, scar tissue restricts circulation. It limits movement, slows adaptation, and reduces the system’s capacity to respond to new conditions. What once protected vitality eventually constrains it. Civilisations that fail to recognise this transition mistake safety for strength and stability for resilience.

This is where the bitter lesson bears directly on the planning of new cities.

If new cities are conceived as finished artefacts, optimised for visual coherence, political equilibrium, or static masterplans, they will fail before they begin. Such cities lock in assumptions about industry, mobility, energy, and labour that will be obsolete within a generation. By contrast, the cities that succeed are designed as expandable systems. They privilege excess capacity over short-term efficiency, modular infrastructure over bespoke solutions, and permissive rules over exhaustive control. They are deliberately incomplete at birth, built to absorb new populations, new industries, and new technologies faster than their rivals. Planning, in this context, is not the imposition of order, but the creation of conditions for continuous adaptation.

The bitter lesson of civilisation, then, is not a moral one. It is structural. Scale beats elegance. Adaptation beats intention. Infrastructure beats ideology. Societies do not lose their future because they choose the wrong ideas, but because they allow the systems that once protected them to harden into constraints.

History shows that renewal does not occur evenly across an entire civilisation. It occurs at the frontier. Frontiers are the spaces where rules are lighter, failure is tolerated, and creative chaos can operate at scale. They are the zones where new institutions, new cities, and new forms of infrastructure are allowed to emerge before they are fully understood or fully regulated. Every civilisation that has escaped stagnation has done so by opening such spaces, not by perfecting what already exists.

The choice facing the West is therefore stark. Either it deliberately creates new frontiers where experimentation, growth, and scale are once again possible, or it allows stagnation to deepen behind systems optimised for a world that no longer exists. The technologies that will shape the next century are already visible. The only remaining question is whether the West has the courage to build the spaces in which they can flourish.

Civilisations do not usually miss these moments because they are defeated. More often, they miss them because they hesitate.

![ROMULLUS | [Sci-Fi] Infrastructure for the West and Her Allies](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/65b3c1f0a4d6295a6ebd4b19/d4a8aeab-602b-41b7-b59f-958880d76a5b/ROMULLUS-61.png?format=1500w)